Scintpreen/Preenscint

WRITTEN AND DESIGNED

AT CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF THE ARTS,

1997

This essay is the result of a writing project at CalArts called Micro Macro. Download a PDF here.

Los Angeles, October 1996. A friend is showing us his graphic design thesis called xhibit, a CD-ROM with a virtual exhibition of digital work created by photographers, illustrators and designers he is friends with. The umbrella topic is Los Angeles. This piece of work is a self-initiated, self-published project that includes editing, writing and form-giving and in this sense represents an impressing example of graphic authorship. On the other hand, his CD-ROM is just an extended form of an art catalog, where he acted as a curator and a writer, but where his design just forms the frame for the real content, the exhibited artwork.

This evening’s audience includes one of the participating artists, a photographer with a CalArts MFA degree, who designs Web sites for a living (and who at least tonight shows merely technical interest); and my roommate, a character animator-director. After my friend hits the “Quit” key, my roommate says, “This looked really beautiful, but to be honest … you guys should keep doing books.” Although he adds “No, I’m just kidding,” I sense a certain arrogant doubt in his comment.

Arrogance, because he knows that feature films, with the help of a gigantic production and marketing expense, are able to evoke more subtle emotions, to create more seducing images and to reach a bigger audience than new media can dream of within the next years. Doubts, because he as a storyteller does not believe in an (inter-)active audience but in one that wants to be swept away and overcome, that wants to keep being consumers of pre-packaged culture. Even more so, he wants to maintain the control and authority the movie industry and the audience provides for him.

Introduction

At a time when the profession of graphic design is about to redefine itself as an academic field and to discuss a status of its theory as a liberal art, at a time when it nevertheless feels the need to court its audience’s understanding and appreciation, the specter of new media appears on the horizon and raises a huge bandwidth of emotions within the graphic design community, everything from fear to temptation, from commitment to apathy, from curiosity to negation — all of these emotions are at the same time nurtured by a general cultural enthusiasm and irritated by the confusion of contemporary culture theory.

Without having the slightest clue where new media will lead us, graphic designers seem — with very few exceptions — to be very eager to board the ship. It hasn’t been figured out whether in the near future our entire body will be used as an intuitive interface to navigate through virtual spaces, or if in fifty years we still access information and guidance using exclusively our eyes and fingers like in today’s Internet (or ATM machines, for that matter). It is not clear, either, to what amount graphic designers will be invited to participate in or able to create new media projects.

In spite of this state of disorientation and unpredictability, graphic designers envision the continent of new media as either the Promised Land, as a sinful temptation, an area to do missionary work in — or simply as a welcome cha(lle)nge.

“It is not self-evident to the world out there that the skills of a graphic designer are critical to the success of new media projects.”

Lorraine Wild, That was then, and this is now: but what is next?,

Emigre, Number 39, 1996, p26.

“Even at the superficial level on which the computer industry understands it, graphic design has a great deal to contribute to digital media.”

William Owen, Design in the age of digital reproduction,

Eye, Number 14, 1994, pp38–39.

The Old World

Why do so many designers want to abandon the continent of print? Partly because they feel that they are receiving too little respect, acceptance and interest by academia and the public. J. Abbott Miller asks in a recent essay in Eye Magazine, “How can we communicate the potential of design to shape experience to the audiences whose experience we are so accustomed to shaping through the act of design?” He claims that, in newspaper articles, design is regarded as being “too rarefied, too little understood, and simply too ordinary to be of importance beyond its professional realm.” At the end of his essay, a little desperate, he finds himself “wanting design to be valued (…) for its sheer ubiquity, for having saturated culture in so many ways.”

In opposition to architecture or film, graphic design just seems to be more basic. In elementary school, children start putting texts on their drawings; later in life people draw garage sale signs and design party invitations. It apparently takes more training, knowledge, people and money to make a movie than to design a poster that works. In consequence, graphic design — if noticed at all — is regarded as a close relative to the stuff everybody basically could do themselves. Letters, soap boxes, book covers and posters seem simply to fall from the sky rather than having been designed by somebody.

If at all, design gets noticed and criticized when it is not invisible; when it is not a humble servant, but an obvious transmitter between the content and the recipient (in the case of simply bad design, manipulative advertising, critical deconstructivist or style-driven design) or if it enters the realm of the content (in the case of the Big Idea or when editing huge amounts of information). In the latter case, one could argue, it ceases to be design anyway and becomes writing or editing.

“If you accord any importance to the everyday,” writes J. Abbott Miller, “then graphic design is right up there with buildings, language and sex.”

But while buildings, language and sex are able to evoke an immense emotional response, nobody ever had an orgasm in front of a poster because of the poster or, to be precise, because of the design of the poster. Usually graphic design acts invisible; it is the content that may move the reader/viewer, whereas the design – if it isn’t viewed in a museum context, but in real life: on the street or in a magazine – is just seen as a necessary and passive carrier of the content. To read the codes of the design would more often than not distract from the content and requires a degree of sophistication which the public doesn’t have in decoding architecture or movies either, but which it doesn’t need for enjoying them — because they are sensually cognizable and emotionally immediate.

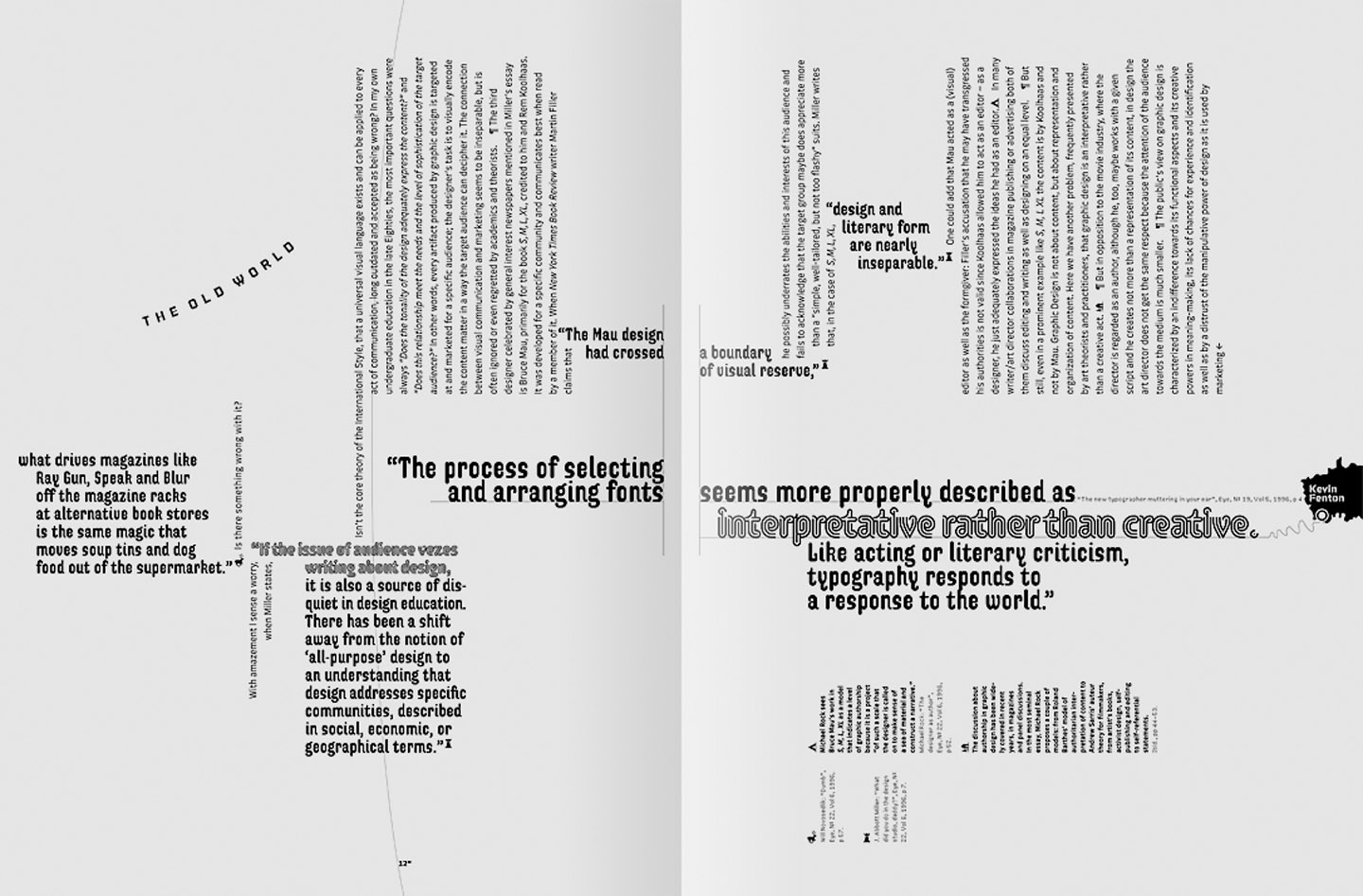

It is not by accident that Miller writes about newspaper articles on David Carson, Fabien Baron and Bruce Mau. In the work of the grand stylists Baron and Carson the design pushes itself very consciously in between content and reader/consumer: The design is part of or, in fact, sometimes is the commodity. Apart from the fact that they get reviewed as celebrities while soap box designers stay anonymous, there is not a big difference between fashion- and style-driven magazine or ad design and marketing-driven packaging, as Will Novosedlik notes: “Not surprisingly, what drives magazines like Ray Gun, Speak and Blur off the magazine racks at alternative book stores is the same magic that moves soup tins and dog food out of the supermarket.”

Is there something wrong with it? With amazement I sense a worry when Miller states, “If the issue of audience vexes writing about design, it is also a source of disquiet in design education. There has been a shift away from the notion of ‘all-purpose’ design to an understanding that design addresses specific communities, described in social, economic, or geographical terms.”

Isn’t the core message of the International Style, that there is something like a universal visual language, long outdated and accepted as being wrong? In my own undergraduate education in the late Eighties, the most important questions were always “Does the tonality of the design adequately express the content?” and “Does this relationship meet the needs and the level of sophistication of the target audience?”

In other words, every artifact produced by graphic design is targeted at and marketed for a specific audience; in consequence, the content has to be adequately visualized. The connection between visual communication and marketing seems to be unseparable, but is often ignored by academics and theorists.

The book S, M, L, XL by Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau was developed for a specific community and communicates best when read by a member of it. When New York Times Book Review writer Martin filler claims that “the Mau design had crossed a boundary of visual reserve,” he possibly underrates the abilities and interests of this audience and fails to acknowledge that the target group maybe doesn’t like “simple, well-tailored, but not too flashy” suits. Miller writes that, in the case of S, M, L, XL, “design and literary form are nearly inseparable;” one could add that Mau acted as an (visual) editor as well as the form-giver: filler’s accusation that he may have transgressed his authorities might not be valid since Koolhaas allowed him to act as an editor — as a designer, he just adequately expressed the ideas he had as an editor.

In many writer/art director collaborations in magazine publishing or advertising, both of them discuss editing and writing as well as designing on an equal level.

But still, even in a prominent example like S, M, L XL the content is by Koolhaas and not by Mau. Graphic Design is not about content, but about representation and organization of content. Here we have another problem, frequently presented by art theorists and practitioners, that graphic design is an interpretative rather than a creative act.

“Without explicitly stating it, much recent discussion assumes that typography is — or can be — a creative act. But because it depends on existing subject matter, the process of selecting and arranging fonts seems more properly described as interpretative rather than creative. Like acting or literary criticism, typography responds to a response to the world.”

Kevin Fenton, The new typographer muttering in your ear,

Eye, Number 19, 1995, p4.

“(Designers) don’t always see the necessity (or have the opportunity) to integrate their personal ideologies into their professional work. They enjoy giving form to ideas. If designers were made of ideas, they’d be their own clients.”

Rudy Vanderlans, Graphic design and the Next Big Thing,

Emigre 39, 1996, p7.

But in opposition to the movie industry, where the director is regarded as an author, although he, too, maybe works with a given script and he creates not more than a representation of its content, in design the art director does not get the same respect because the attention of the audience towards the medium is much smaller.

The public’s view on graphic design is characterized by an indifference towards its functional aspects and its creative powers in meaning-making, its lack of chances for experience and identification as well as by a distrust of the manipulative power of design as it is used by marketing.

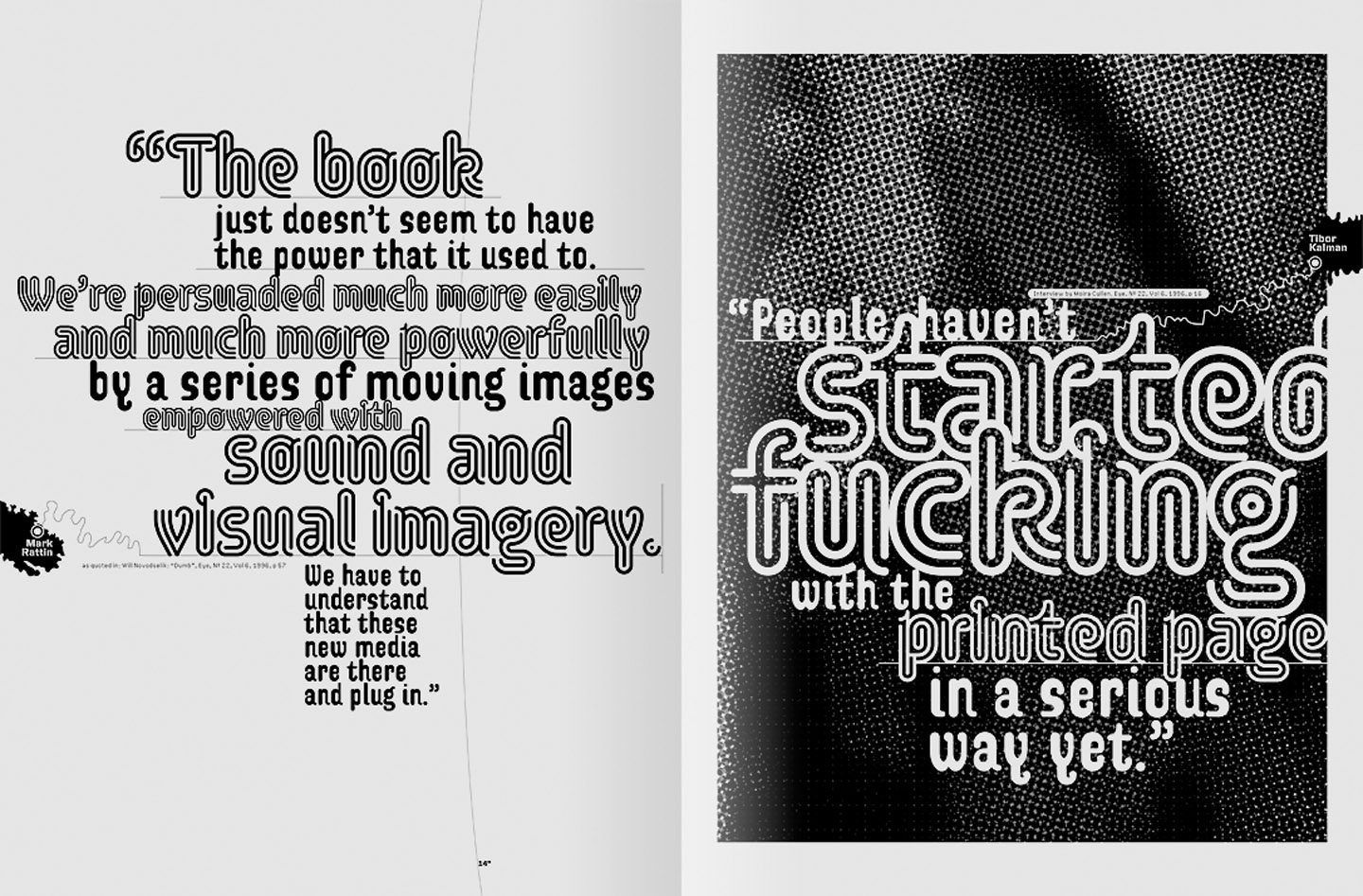

“The book just doesn’t seem to have the power that it used to. We’re persuaded much more easily and much more powerfully by a series of moving images empowered with sound and visual imagery. We have to understand that these new media are there and plug in.”

Mark Rattin as quoted in: Will Novosedlik, Dumb,

Eye, Number 22, 1996, p57.

“People haven’t started fucking with the printed page in a serious way yet.”

Tibor Kalman, Interview by Moira Cullen,

Eye, Number 22, 1996, p16.

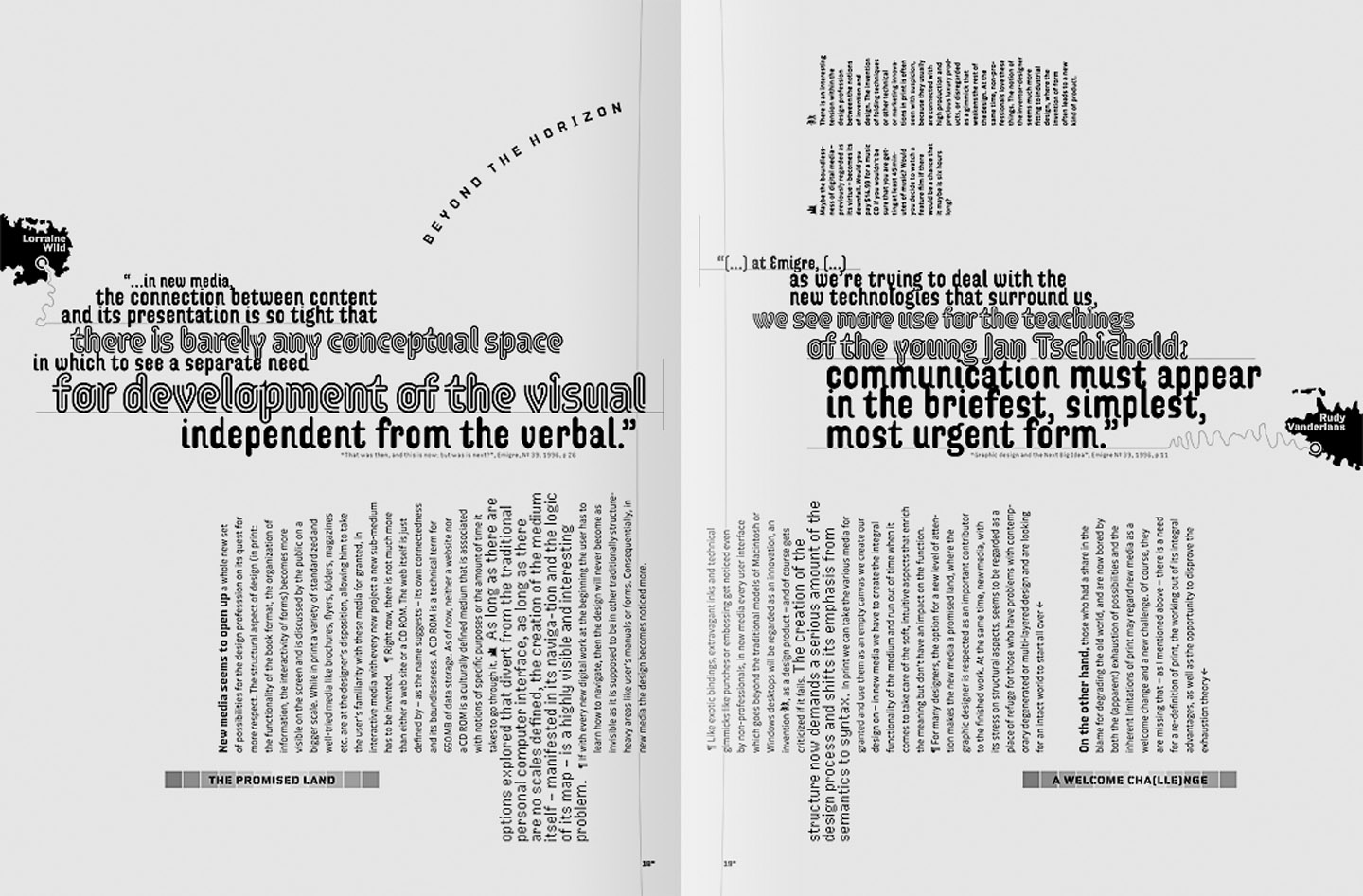

“… in new media, the connection between content and its presentation is so tight that there is barely any conceptual space in which to see a separate need for development of the visual independent of the verbal.”

Lorraine Wild, That was then, and this is now: but what is next?,

Emigre, Number 39, 1996, p26.

Beyond the Horizon

THE PROMISED LAND

New media seems to open up a whole new set of possibilities for the design professsion on its quest for more respect. The structural aspect of design (in print: the functionality of the book format, the organization of information, the interactivity of tax reports) becomes more visible on the screen and is discussed by the public on a bigger scale. While in print a variety of standardized and well-tried media like brochures, flyers, folders, magazines etc. are at the designer’s disposition, allowing him to take the user’s familiarity with these media for granted, in digital design a new medium has to be invented with every new project.

Right now, there is not much more than either a Web site or a CD ROM. The Web itself is just defined by — as the name suggests — its own connectedness. CD ROMs are rather technical carriers of data than a culturally defined medium that is associated with notions of specific purposes.

(Maybe the boundlessness of digital media — previously regarded as its virtue — becomes its downfall. Would you pay $14.99 for a music CD if you wouldn’t be sure that you are getting at least 45 minutes of music? Would you decide to watch a feature film if there would be a chance that it maybe is six hours long?)

As long as there are options explored that divert from the traditional personal computer interface, as long as there are no scales defined, the creation of the medium itself — manifested in its navigation and the logic of its map — is a highly visible and interesting problem. If, with every new digital piece, the user has to learn how to navigate, then the design will never become as invisible as it is supposed to be in other traditionally structure-heavy areas like time-tables or forms. In consequence, in new media the design becomes noticed more.

Just like in print exotic bindings, extravagant inks and technical gimmicks like punches or embossing get noticed even by non-professionals, in new media every user interface that goes beyond the traditional models of Macintosh or Windows systems will be regarded as an innovation, an invention, as a design product — and of course gets criticized if it fails. The creation of the structure represents a large part of the design process and shifts its emphasis from semantics to syntax. In print, we can take the various media for granted and use them as an empty canvas we create our design on. In new media, we have to create the integral functionality of the medium and quickly run out of time when it comes to take care of the soft, intuitive aspects that enrich the meaning but don’t have an impact on the function.

For many designers, the option for a new level of attention makes the new media a Promised Land, where the graphic designer is respected as an important contributor to the finished work. At the same time, new media, with its stress on structural aspects, seems to be regarded as a place of refuge for those who have problems with contemporary degenerated or multi-layered design and are looking for an intact world to start all over.

A WELCOME CHA(LLE)NGE

On the other hand, those who had a share in the blame for degrading the old world, and are now bored by both the (apparent) exhaustion of possibilities and the inherent limitations may regard new media as a welcome change and a new challenge. Of course, they are missing that — as I mentioned above — there is a need for a re-definition of print, the working out of its integral advantages, as well as the opportunity to disprove the exhaustion theory.

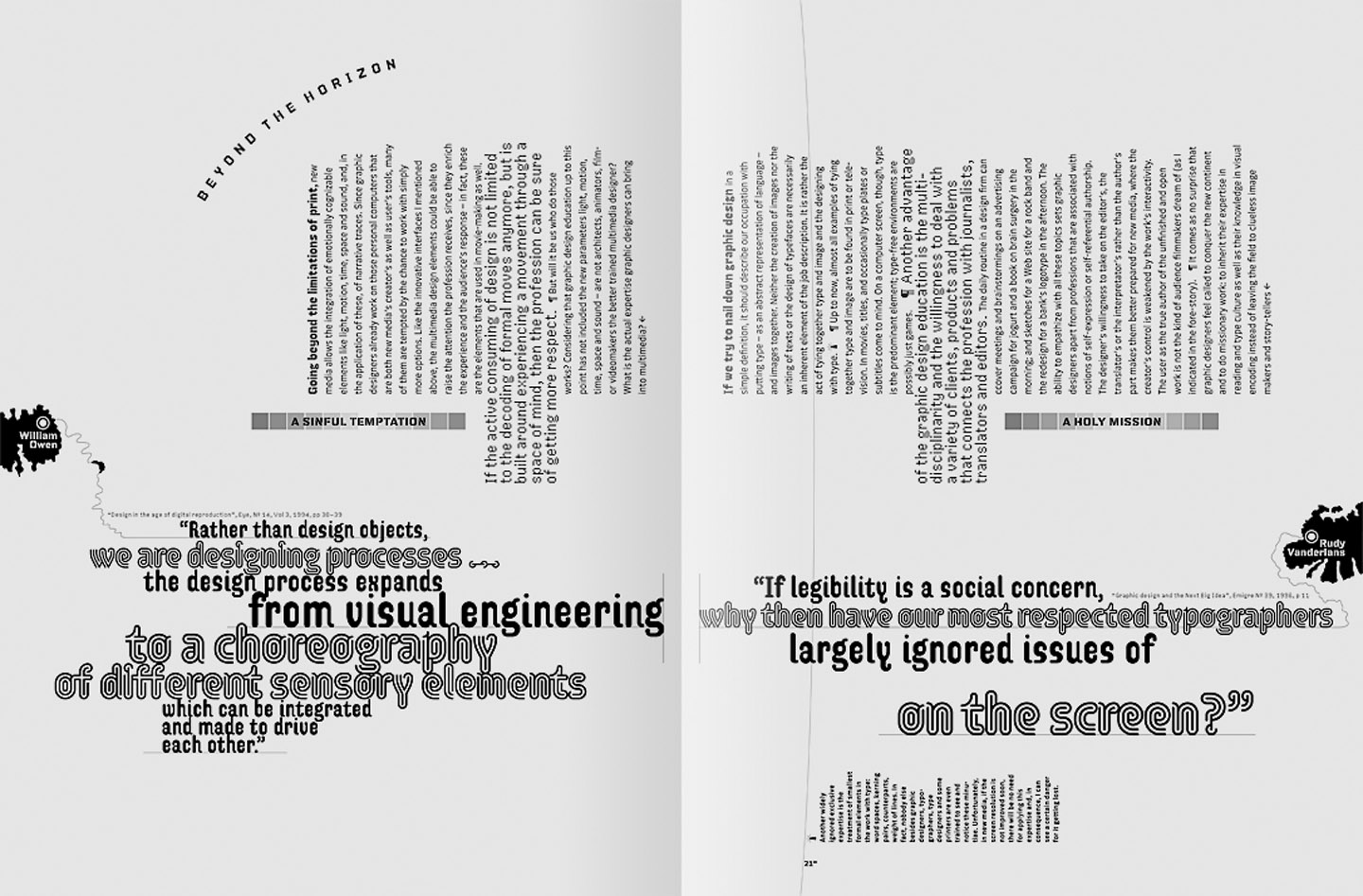

A SINFUL TEMPTATION

“Rather than design objects, we are designing processes … the design process expands from visual engineering to a choreography of different sensory elements which can be integrated and made to drive each other.”

William Owen, Design in the age of digital reproduction,

Eye, Number 14, 1994, pp38–39.

Going beyond the limitations of print, new media allows the integration of emotionally cognizable elements like light, motion, time, space and sound, and, in the application of these, of narrative traces. Since graphic designers already work on those personal computers that are both new media’s creators’ as well as users’ tools, many of them are tempted by the chance to work with simply more options. Like the innovative interfaces I mentioned above, the multimedia design elements could be able to raise the attention the profession receives, since they enrich the experience and the audience’s response — in fact, these are the elements that are used in movie-making as well. If the active consumption of design is not limited to the decoding of formal moves anymore, but is built around experiencing a movement through a space of mind, then the profession can be sure of getting more respect

But will it be us who get to do those projects? Considering that graphic design education up to this point has not included the new parameters light, motion, time, space and sound — are not architects, animators, film- or videomakers the better-trained multimedia designers? What is our actual expertise we can bring into multimedia?

A HOLY MISSION

“If legibility is a social concern, why then have our most respected typographers largely ignored issues of legibility on the screen?”

Rudy Vanderlans, Graphic Design and the Next Big Thing,

Emigre, Number 39, 1996, p11.

If we try to nail down graphic design in a simple definition, it should describe our occupation as putting type — as an abstract representation of language — and images together. Neither the creation of images nor the writing of texts or the design of typefaces are a necessarily inherent element of the job description. It is rather the act of tying together type and image and the designing with type.

(Another widely ignored exlusive expertise is the treatment of smallest formal elements in the work with type: word spaces, kerning pairs, counterparts, weight of lines. In fact, nobody else besides graphic designers, typographers, type designers and some printers are even trained to see and notice these minutiae. Unfortunately, in new media, if the screen resolution is not improved soon, there will be no need for applying this expertise and, in consequence, I can see a certain danger for it getting lost.)

Up to now, almost all examples of tying together type and image are to be found in print. In movies and television, titles and occasionally type plates or subtitles come to mind. On a computer screen, though, type is the predominant element, type-free environments are possibly just games.

Another advantage of the graphic design education is the multi-disciplinarity and the willingness to deal with a variety of clients, products and problems that connects the profession with journalists, translators and editors. The daily routine in a design firm can cover meetings and brainstormings on an advertising campaign for jogurt and a book on brain surgery in the morning; and sketches for a Web site for a rock band and the redesign for a bank’s logotype in the afternoon. The ability to empathize with all these topics separates graphic designers from professions that are associated with notions of self-expression or self-referential authorship. The designer’s acceptance of the editor’s, translator’s or interpretator’s rather than the author’s part makes them better prepared for new media, where the creator’s control is weakened by the work’s interactivity. The user as the true author of the unfinished and open work is not the kind of audience filmmakers dream of (as I indicated in the fore-story).

It comes as no surprise that graphic designers feel called to conquer the new continent and to do missionary work there: to pass on their expertise in reading and type culture as well as their knowledge in visual communication instead of leaving the field to clueless image makers and story-tellers.

“(…) the process of large group or team projects in multimedia has less to do with the division of labor in print production, and is much more akin to collaborative enterprises, such as theatrical production, TV production, or movie-making int he entertainment industry. And in those enterprises, the identity and independence of individuals responsible for the visual presentation (…) are secondary in both the hierarchy of production and in the point of view of the audience to the vision or authorship of the director (and perhaps the screenwriters). While the accomplishments of the visual collaborators may be highly celebrated and compensated, the ability to launch current and future projects rests with the authors — the directors and screenwriters.”

Lorraine Wild, That was then, and this is now: but what is next?,

Emigre, Number 39, 1996, p28.

The Voyage

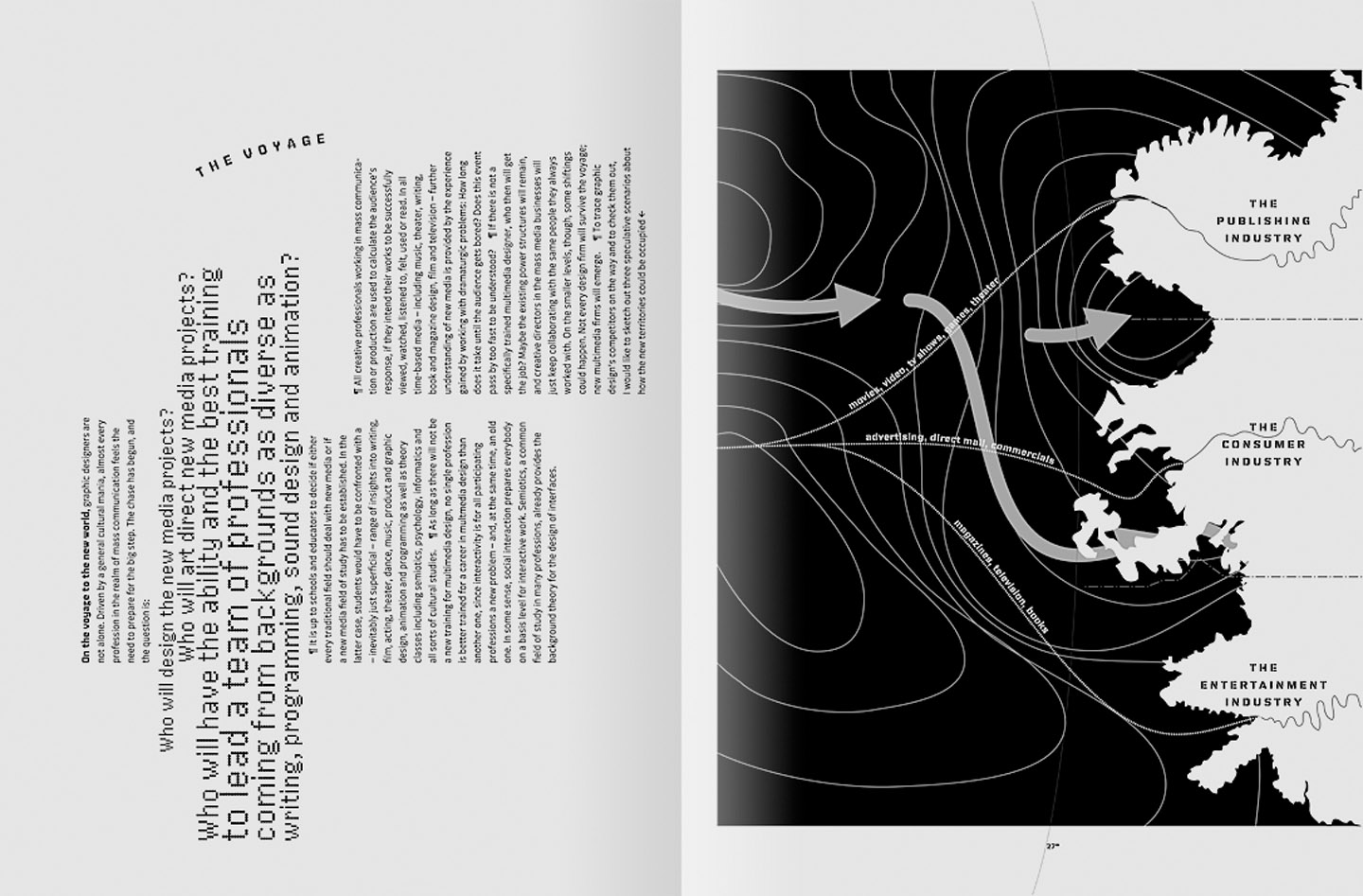

On the voyage to the new world, graphic designers are not alone. Driven by a general cultural mania, almost every profession in the realm of mass communication feels the need to prepare for the big step. The chase has begun, and the question is: Who will design the new media projects? Who will art direct new media projects? Who will have the ability and the best training to lead a team of professionals coming from backgrounds as diverse as writing, programming, sound design and animation?

It is up to schools and educators to decide if either every traditional field should deal with new media or if a new media field of study has to be established. In the latter case, students would have to be confronted with a — inevitably just superficial — range of insights into writing, film, acting, theater, dance, music, product and graphic design, animation and programming as well as theory classes including semiotics, psychology, informatics and all sorts of cultural studies.

As long as there will not be a new training for multimedia design, no single profession is better trained for a career in multmedia design than another one, since interactivity is for all participating professions a new problem — and, at the same time, an old one. In some sense, social interaction prepares everybody on a basis level for interactive work. Semiotics, a common field of study in many professions, already provides the background theory for the design of interfaces.

All creative professionals working in mass communication or production are used to calculate the audience’s response, if they intend their works to be successfully viewed, watched, listened to, felt, used or read. In all time-based media — including music, theater, writing, book and magazine design, film and television — further understanding of new media is provided by the experience gained by working with dramaturgic problems: How long does it take until the audience gets bored? Does this event pass by too fast to be understood?

If there is not a specifically trained multimedia designer, who then will get the job? Maybe the existing power structures will remain, and creative directors in the mass media businesses will just keep collaborating with the same people they always worked with. On the smaller levels, though, some shiftings could happen. Not every design firm will survive the voyage; new multimedia firms will emerge.

To trace graphic design’s competitors on this journey, I would like to sketch out three speculative scenarios about how the new territories could be occupied.

Model A:

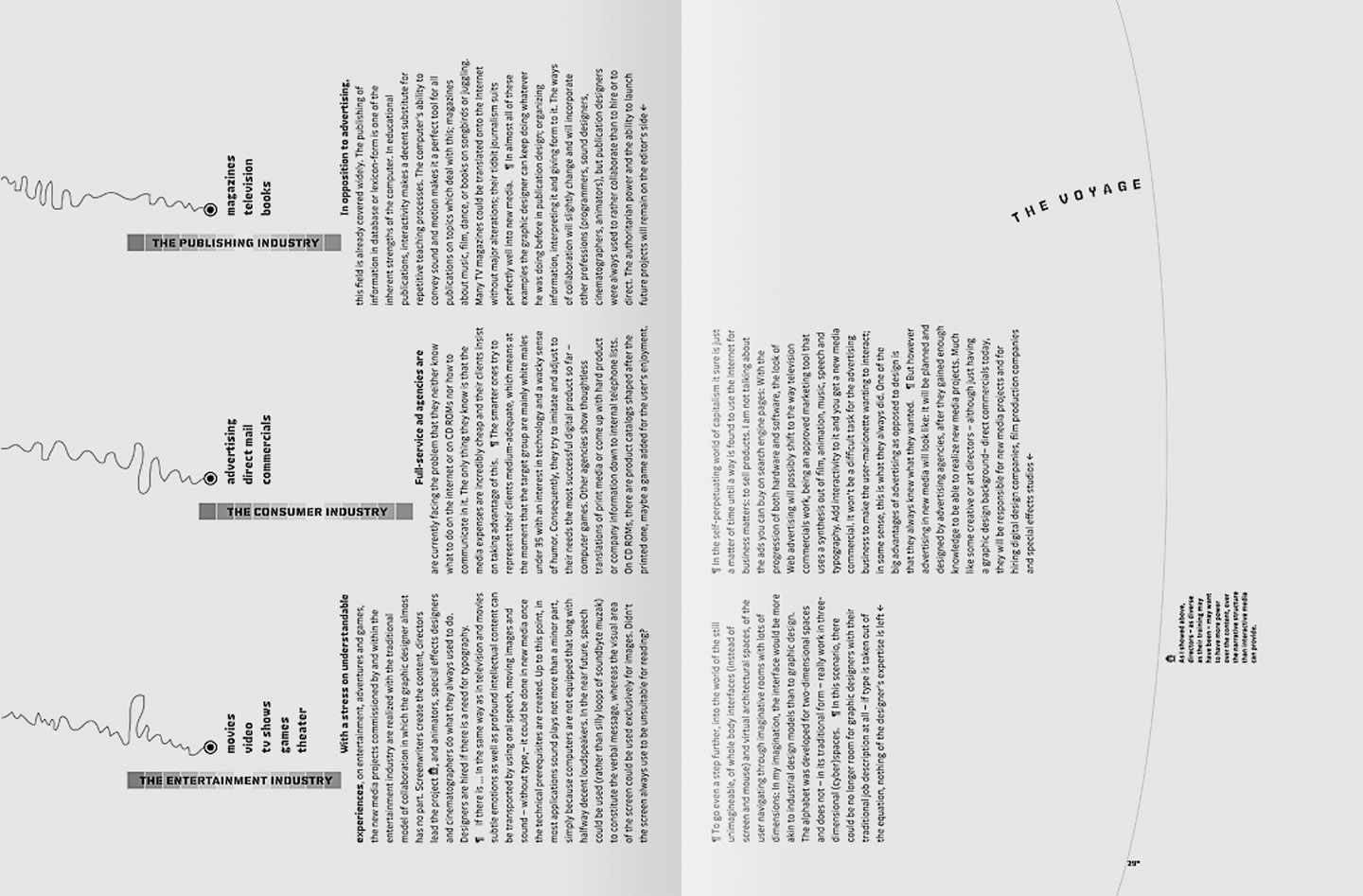

The Entertainment Industry

Movies, Television Shows, Music Promos, Games, Theater

The Entertainment Industry

Movies, Television Shows, Music Promos, Games, Theater

With a stress on understandable experiences, on entertainment, adventures and games, the new media projects commissioned by and within the entertainment industry are realized through the traditional model of collaboration in which the graphic designer almost has no part. Screenwriters create the content, directors lead the project (although they may want to have more power over the content, over the narrative structure than interactive media can provide). Animators, special effects designers and cinematographers do what they always used to do. Designers are hired if there is a need for typography.

If there is a need … In the same way as in television and movies subtle emotions as well as profound intellectual content can be transported by using oral speech, moving images and sound — without type —, it could be done in new media once the technical prerequisites are created. Up to this point, in most applications sound plays not more than a minor part, simply because computers haven’t been equipped with halfway decent speakers. In the near future, speech could be used (rather than silly loops of soundbyte muzak) to constitute the verbal message, whereas the visual area of the screen could be used exclusively for images. Didn’t the screen always use to be unsuitable for reading?

To go even a step further, into the world of the still unimagineable, of whole body interfaces (instead of screen and mouse) and virtual architectural spaces, of the user navigating through imaginative rooms with lots of dimensions: In my imagination, the interface would be more akin to industrial design models than to graphic design. The alphabet was developed for two-dimensional spaces and does not — in its traditional form — really work in three-dimensional (cyber)spaces.

In this scenario, there could be no longer room for graphic designers with their traditional job description at all — if type is taken out of the equation, nothing of the designer’s expertise is left.

Model B:

The Advertising Industry

Print Advertising, Direct Mail, Television Commercials, Radio Commercials

The Advertising Industry

Print Advertising, Direct Mail, Television Commercials, Radio Commercials

Full-service advertising agencies are currently facing the problem that they neither know what to do on the internet or on CD ROMs nor how to communicate in it. The only thing they know is that the media expenses are incredibly cheap and their clients insist on taking advantage of this.

The smarter ones try to represent their clients medium-adequate, which means at the moment that the target group are mainly white males under 35 with an interest in technology and a wacky sense of humor. Consequently, they try to imitate and adjust to their needs the most successful digital product so far — computer games. Other agencies show thoughtless translations of print media or come up with hard product or company information down to internal telephone lists. On CD ROMs, there are product catalogs shaped after the printed one, maybe a game added for the user’s enjoyment.

In the self-perpetuating world of capitalism it sure is just a matter of time until a way is found to use the Internet for business matters: to sell products. I am not talking about the ads you can buy on search engine pages: With the progression of both hardware and software, the look of Web advertising will possibly shift to the way television commercials work, being an approved marketing tool that uses a synthesis out of film, animation, music, speech and typography. Add interactivity to it and you get a new media commercial. It won’t be a difficult task for the advertising business to make the user-marionette wanting to interact; in some sense, this is what they always did. One of the big advantages of advertising as opposed to design is that they always knew what they wanted.

But however advertising in new media will look like: It will be planned and designed by advertising agencies, after they gained enough knowledge to be able to realize new media projects. Much like some creative or art directors — although just having a graphic design background — direct commercials today, they will be responsible for new media projects and for hiring digital design companies, film production companies and special effects studios.

Model C:

The Publication Industry

Magazines, Television, Books

The Publication Industry

Magazines, Television, Books

Unlike advertising, this field is already covered widely. The publishing of information in database or lexicon-form is one of the inherent strengths of the computer. In educational publications, interactivity makes a decent substitute for repetitive teaching processes. The computer’s ability to convey sound and motion makes it a perfect tool for all publications on topics which deal with this; magazines about music, film, dance, or books on songbirds or juggling. Many TV magazines could be translated onto the Internet without major alterations; their tidbit journalism suits perfectly well into new media.

In almost all of these examples the graphic designer can keep doing whatever he was doing before in publication design; organizing information, interpreting it and giving form to it. The ways of collaboration will slightly change and will incorporate other professions (programmers, sound designers, cinematographers, cutters), but publication designers were always used to rather collaborate than to hire or to direct. The authoritarian power and the ability to launch future projects will remain on the editor’s side.

The New World

“New media will go ahead without our participation, which for many designers may be ok. The price of participation may actually be the end of graphic design as we know it, and the price of separation will probably be the maintenance of the low profile of graphic design in the public consciousness.

Lorraine Wild, That was then, and this is now: but what is next?,

Emigre, Number 39, 1996, pp32–33.

Assuming that a mix of all three of the scenarios will happen, most graphic designers can keep their positions if they only learn how to deal with the new technologies. Some designers will keep doing form-giving, only switching their expertise to the screen. For art-directors who are used to work on a variety of diverse projects like print, TV commercials, magazines and direct-mail, multimedia is just another item on the list. Conceptually oriented designers who had to deal with unrelated tasks like editing, writing or video anyway, regard new media as a new challenge, including new ways of collaborations with people they never had to talk to before.

However, not all of the designer’s desires will be fulfilled. As I pointed out, the audience’s interest for the functionality of the navigation will last only as long as there are no standards defined or as long as there is still an interest in the novelty of digital media.

Additionally, not in every scenario it is clear that the big structure will be created by graphic designers: The only field of the profession that seems to be able to gain or keep their authoring position is design in advertising. In publishing or entertainment, there will be neither a chance for designers to launch projects nor an opportunity to get their hands on work with sound and live action; this will — and should — be done by trained professionals in a collaborative enterprise led by editors or directors.

In low-budget and self-published projects, it is the designer’s ability to work with the new parameters that decides if the audience gets more evolved emotionally. But in this instance, the low-budget designer slips into the suit of sound engineers and cinematographers: It will not be the graphic design aspects of multimedia that evoke emotions — moving type is simply not able to make an impact as touching as live action, music or speech; it might even fail compared to the sensual power of a huge silkscreened poster with fluorescent or metallic inks.

But still, as long as there is type needed in new media, it is the design profession’s task to add their knowledge in typography and visual semiotics to the process and to keep their influence on mass communication, without trying to get commissions for sound design or story-telling. A basic knowledge of non-design multimedia parameters is a must, but apart from collaborative work processes it is typography where the graphic designer has the authority to decide and the duty to criticize.

In new media teams where the art directing and the visual design maybe is done by people with television or film backgrounds, the position of the type director — having almost disappeared in print businesses — could be revived, a position being solely responsible for every instance where typography is used. Graphic design as we know it may die together with print, whereas typography may survive the voyage into the new world.

----------------------------------------

Writing, Design & Typography: Jens Gehlhaar

Consultation: Lorraine Wild

California Institute of the Arts, School of Art,

Program in Graphic Design, Valencia